This is the text for a talk I gave at the Galpin Society Conference, Music Faculty, Oxford, on 26th July 2013

(edit in progress, click on the pictures for more detailed viewing)

While it is evident that most objects bear the marks of their use, traces of their journey through time remaining as clues inscribed in their fabric, old stringed instruments can be surprisingly coy and tricky to read for a variety of reasons.

While it is evident that most objects bear the marks of their use, traces of their journey through time remaining as clues inscribed in their fabric, old stringed instruments can be surprisingly coy and tricky to read for a variety of reasons.

Use, wear and tear, damage, the need for repair, the need to conceal repairs, adaptations or transformations to suit the needs of a specific individual or reflecting stylistic changes and fashions, commercial pressure and even pure experimentation, may all act upon these instruments. To what extent can one construct a valid history of an instrument from the sometimes contradictory clues which are now evident?

Since we are talking about ‘reading’ musical instruments, it seems fitting to also ‘read’ actual printed texts which outline, describe, prescribe or justify processes which have taken place. In the 19th c. and 20th c. intervention was particularly rife, relentless and inventive, and what follows are a few passages which may reflect what might have happened to historical instruments.

Speaking very generally, one could say that in a given context, ideas and ideologies indeed shape the world, as well as are shaped by it, and speaking specifically about restoration, the well-known assertion by Cesare Brandi “Restoration is, after all, criticism” points towards the peculiar type of authority (one could say even authorship!) which restorers exert at some point in the life of an object, an object which all being well will survive their actions and outlive their restorer

=========================

I mentioned experimentation as a motive for action: the following passage comes from a short book published in translation in 1895 as ‘The Violin and the Art of its Construction’ by the Berlin-based violin maker and restorer August Riechers. The work is dedicated to his friend the violinist Joseph Joachim.

In this passage he refers to a specific and very active relationship with a particular violin bow by the great and prolific bow-making innovator Francois Xavier Tourte.

One can imagine Joachim’s raised eyebrows when he tried the bow after the work was done!

This is an unusually candid account, is extreme both in the operation performed, and in the questionable reasoning which accompanies it, but I can testify that in my contact with old instruments and bows of nearly 35 years, I have come across quite a few pieces which definitely bear the marks of such an enthusiastic and unbridled spirit of intervention.

It is touching too: Riechers seems like a tragic figure out of an E.T.A. Hoffmann story, with a subjective and potent take on the material world, working from and confirming an impeccably ludicrous logic.

=======================

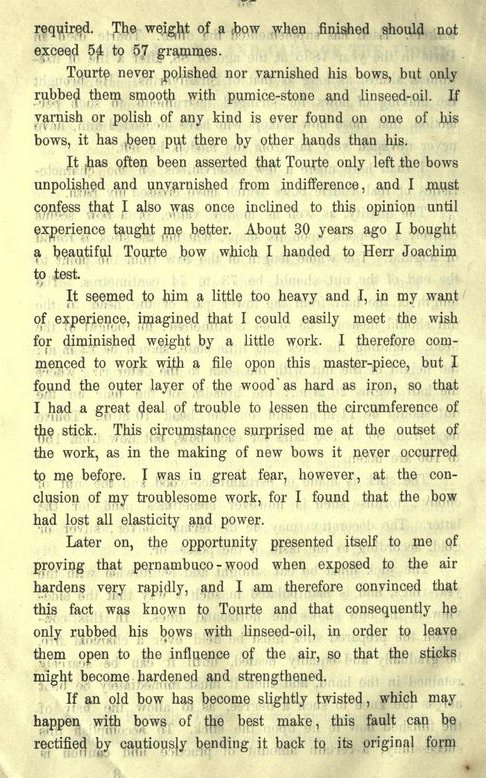

About changes in style and fashion motivating major alterations, what follows are translated extracts from Auguste Tolbecque’s ‘L’Art du Luthier’ published in 1903 in Niort.

Tolbecque was a musician and scholar, a friend of Saint-Saens and a pioneer researcher in early music. He also trained as a luthier, he was a close friend of Gustave Bernardel, so had a direct link with the main stream of what I might describe (revealing my own bias) as the French positivist interventionist 19th century school of restoration. He is an insightful writer, and the description of the processes goes also with reflections on the reasons behind them, and surprising hints of irony occasionally come to the surface.

Let’s have him speak first in his ironic vein about the fashion of his times for ‘all things Stradivari’,

“Nowadays admiration borders on fetishism: and as you can imagine, commerce won’t be sidelined: Then comes wholesale imitation, one copies the master in all aspects of his work, in all the proportions of his instruments: one even attempts to make Stradivarius’s out of the productions from other luthiers, whose work relates only distantly to those of the Master.”

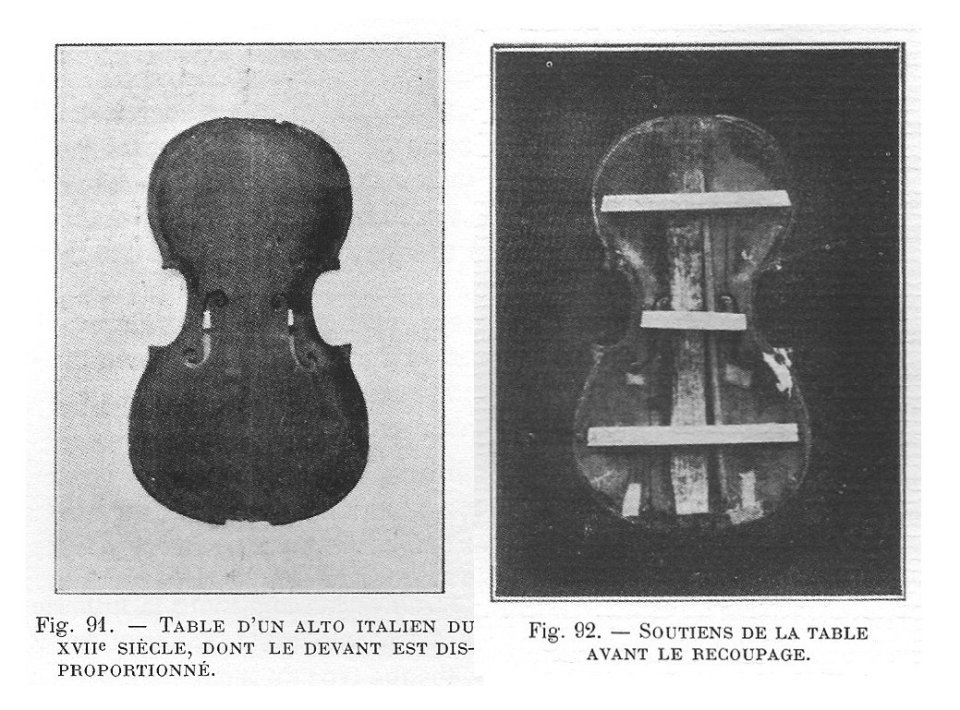

Now about the process of the widespread practice of the cutting down of old instruments:

” when it comes to cellos, the top bout was generally too broad, making the higher positions difficult”

“some luthiers attempted, through cutting down, to bring back over-sized instruments to the proportions of Stradivarius”

“The first attempts were clumsy! So many beautiful instruments were massacred by unskilled and inexperienced workers! They generally were content to nibble table and back according to a more or less deficient pattern, without consideration of edges, fluting and purfling, so these resizings in the end bore neither resemblance to the original nor to the model which they emulated.”

then follows his account of the history of the bass violin and the first appearance of the cello, after which here he is talking about ‘cutting down’ in more detail:

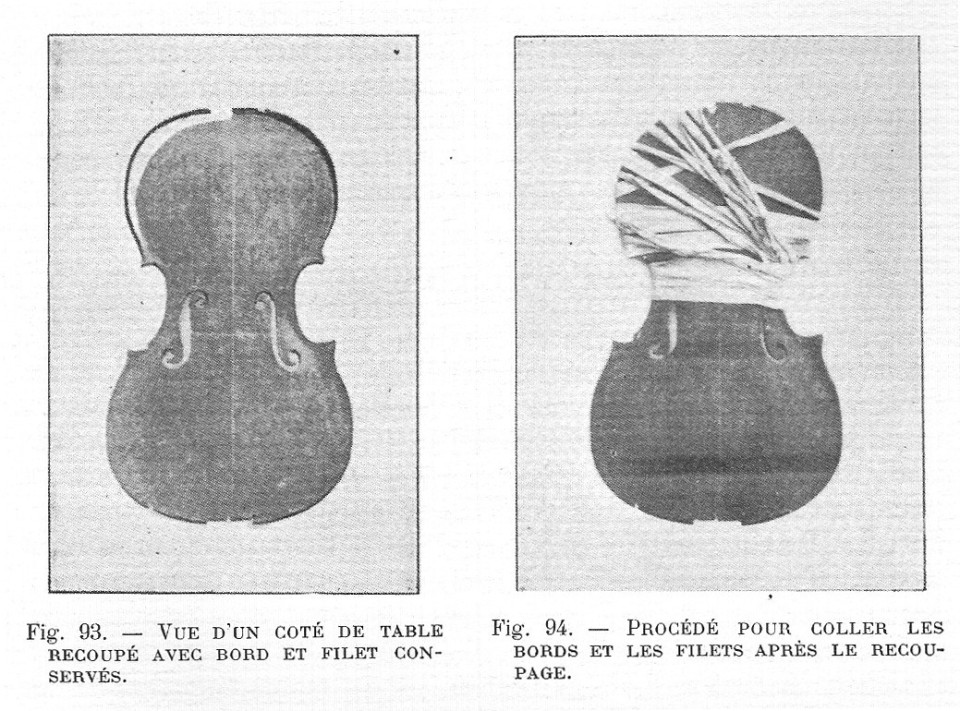

“The Parisian luthiers did a number of these size modifications, in order to bring back to manageable and playable dimensions instruments which would have been either misshapen or too large. But at the same time they did this with tact, keeping the original edges and purfling whilst perfecting the proportions. I can mention the most skilled at this: Lupot, Chanot, Gand, Bernardel, and above all, my master Victor Rambaux, who had an unchallenged reputation for this type of work.

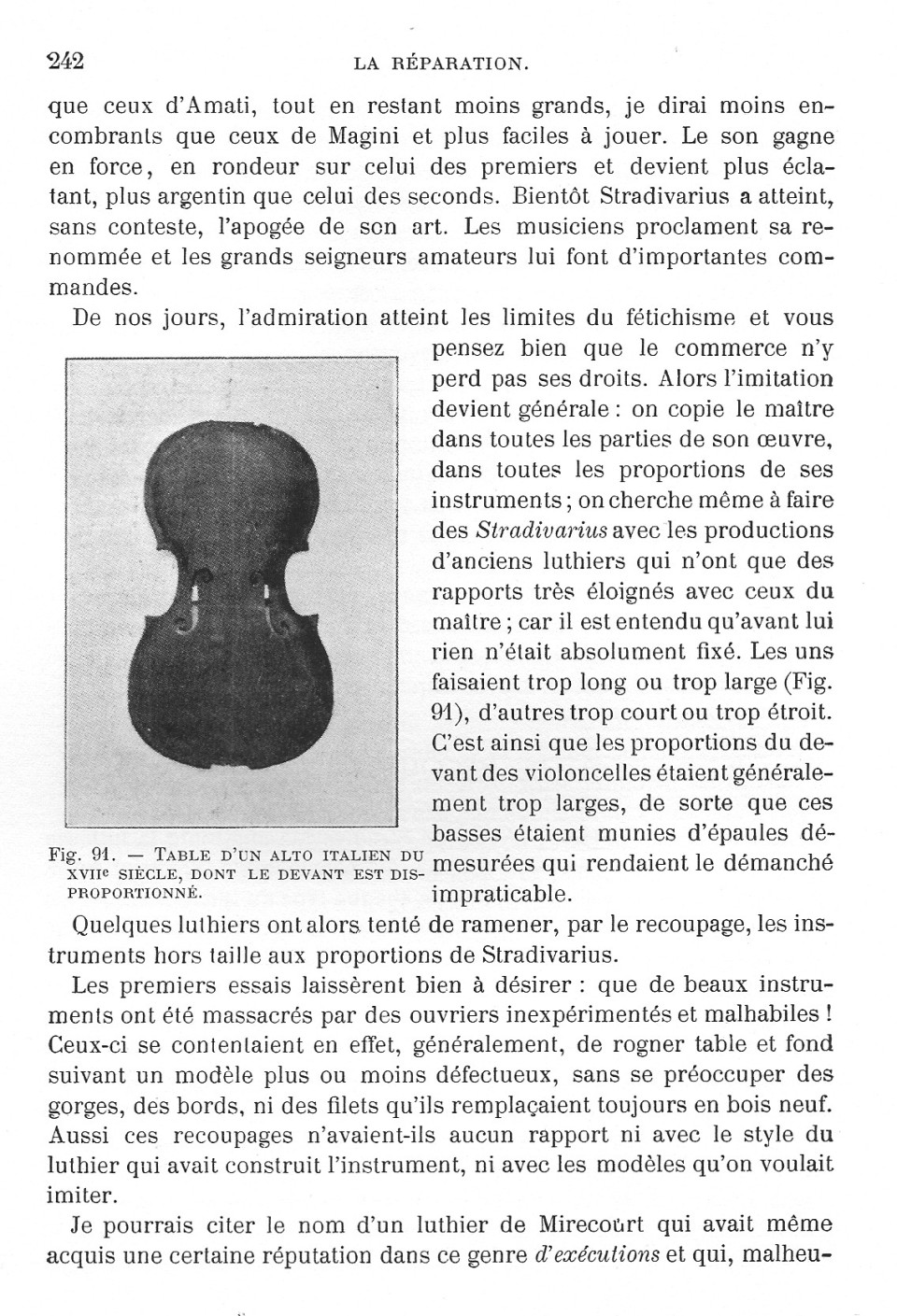

I am coming to the actual operation:

Let’s suppose we need reduce the top bout of a bass (which is the most frequent operation), in order to bring the stop-length down to its ordinary measure of 40cm.

After having opened the instrument, […]one will trace the contour on a piece of white card, will mark the centre line, mark the place of the f-hole notches with a perpendicular line from which the desired stop length will be worked out. One will then mark out the new outline, taking into account that the edge and purfling will need to be reapplied to the table in its new shape. One will mark the line out on the table and proceed: to start with a fine fret saw first removing edge and purfling, starting from the top block all the way to the corner block, making sure that this edge stays attached to the table at the place where the section to be removed is tapered to a point. After which comes the ablation of the portion of table due to disappear. I do not need to add that knife and file will be put to good use to ensure a perfect joint between the preserved edge and the reduced table. Prior to sawing, one will have glued three strengthening struts (see pic) […]

The edge will be glued onto the table, and held with a piece of cloth tape wrapped several times around the table, making sure that the edge is well in register with the table. [..]

after the edges are re-positioned, they will need to be supported, removing half their thickness first and applying half edging to them and also to the portion of table which has been refashioned.. This will give lasting strength to this important piece of work.”

Ironically the photos (which show the cutting down of a large viola, not a cello) have been slightly doctored in the book, they themselves have undergone some sort of restoration and there is a bit of detective work which could be done on that!

Words used are worth noting for their normative character: ramener, to bring back, (paradoxical, considering that more often than not it would consist of taking a 17th c. instrument and to change it in the 19th c. to a pattern derived from an 18th c. model!!). Hors-taille literally out of size, over-size; also, tact; and ordinaire, here meaning standard, referring to a measurement.

Should you be inclined, Tolbecque can also teach you how to enlarge instruments which are too short!

For those who believe these ideas belong in a distant past, I can also quote from the book ‘Les Violons’ (a catalogue from the 1995 Paris Exhibition of 17th and 18th c. Venitian Instruments), where a leading French luthier makes the following statement as part of a debate between experts:

[..]it becomes clear that [..] it is the body of sound which really makes a virtuoso. That is what soloists strive for. This also explains why cellos made in the period we are speaking about have been cut down in size-so as to give the sound more body and also make the instrument easier to play.

==============================

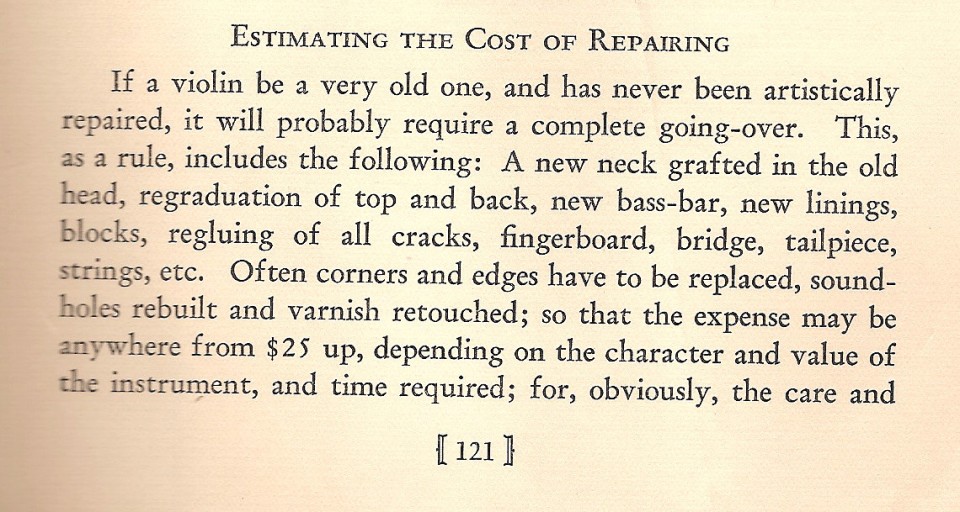

Now for some insight into an unmistakably commercial outlook on restoration: the above passage is from a catalogue dated 1926, from the instrument manufacturers and dealers in fine antique violins Lyon and Healy in Chicago.

Now for some insight into an unmistakably commercial outlook on restoration: the above passage is from a catalogue dated 1926, from the instrument manufacturers and dealers in fine antique violins Lyon and Healy in Chicago.

This is an interesting document, both in content and presentation: it conveys a very ‘old world’ look through the layout and typeface, but is modern in its reassuring tone and sense of certainty. It is a true marriage between old values, and mass production and standardisation.

===========================

Now to a few pictures: here are three images of details of violins by Francesco Ruggieri.

- This first one is basically in good condition, but has had a few repairs and modernisations (it is in the Ashmolean Museum collection),

- The second one (which must have been a complete wreck at one stage in its life) has had the sort of treatment advocated by Lyon and Healy, but done quite sensitively and also visibly by the English firm W.E. Hill & Sons probably shortly after the Second World War.

![]() The table edges and under-edges are new, complete with painted grain lines to approximately match the old ones, there are many crack repairs and several sections of ribs are new, and it is pretty much completely doubled with patches on the inside. (click here for more photos of this violin)

The table edges and under-edges are new, complete with painted grain lines to approximately match the old ones, there are many crack repairs and several sections of ribs are new, and it is pretty much completely doubled with patches on the inside. (click here for more photos of this violin)

- The third one, with a dark layers of patina on the table, which was also in quite bad condition has had the more modern historically informed, respectful, detailed and lengthy restoration which is increasingly the norm.

This current practice which more often than not aims to result in a seamless-ness between new and old, is underpinned by very careful matching of materials and shapes, and is highly conscious of stylistic diversity and specificity. It satisfies the needs of a cultured market, and has its large cost justified by the huge prices which the objects command.

====================

To prepare for this short talk has made me ponder about my own ideas and practice, which are inescapably very much of their time. Minimal and appropriate intervention is certainly at the heart of modern practice, and this I don’t hesitate to call good; however, for all its aspiration to elegance and reverence to the intention of the maker, the seamless-ness and carefully orchestrated mock transparency of most of 21st Century restoration may prove to be a nightmare for future historians wishing to interrogate the objects afresh, rendering the actual history pretty much opaque.

So to end, going back to this construct I started from of ‘reading musical instruments’, it is important to challenge the assumption that one can read them: as we know our own vantage point is necessarily limited, conditioned by its position in time, however well-informed we might think we are; and also to challenge the assumption that one cannot read or that we are condemned to mis-read, or rather condemned by the inescapability of our misreading: after all, almost completely rubbed out fragments written in several partially incomprehensible languages still carry potential meaning.

(After this talk, the questions raised by the audience and the short debate which followed touched mostly on the practice of documentation of restoration )

Bruno Guastalla 2013

Comments are welcome: this very short talk barely hinted at a few ideas, which have been explored in much greater depth by many people in many fields. I would be good to have a bibliography at the bottom of this page, and I would be grateful to readers to point towards other sources of information and debate. I should mention The Conservation, Restoration and Repair of Bowed Instruments and Their Bows which has been instrumental in shifting my own perspective on these activities.